The Zero was designed by a team under the direction of a brilliant young aeronautical engineer, Jiro Horikoshi. Mitsubishi had the foresight to send Horikoshi to work and observe at aircraft factories in Europe and the U.S. in 1929,flush riveting, a production technique the Japanese would subsequently use on the Zero at a time when American air framers were just discovering its low-drag advantage. In order to fight not only the already-overmatched Chinese but also the Pacific war against the U.S. that was beginning to look inevitable, The Japanese would never have attacked Pearl Harbor if they hadn’t had the Zero.

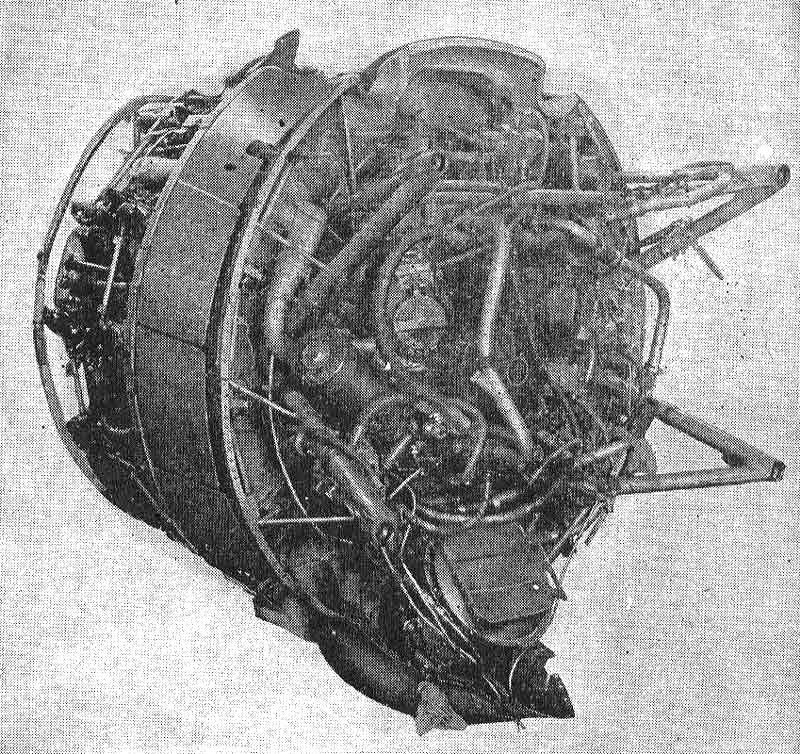

British and German manufacturers were cranking out 1,200-hp engines, with 2,000 hp visible on the horizon. So Horikoshi needed to make his new fighter super light, which he did in part by having lightening holes cut and drilled through every internal airframe part possible—a technique that race car builders would recognize immediately. In fact, Horikoshi could be called the Colin Chapman of aircraft designers; Chapman was the Lotus designer whose mantra was “simplicate and add lightness.” As a result, the Zero was the fastest 1,000-hp, radial-engine fighter ever produced—but one with a number of single-point-failure locations that, if hit, could bring down the airplane. The Zero’s designers considered armour unnecessary because they didn’t think anybody would be able to put any rounds into the fighter. Maybe a lucky shot here and there, but not enough of a danger to compromise the design’s lightness. Little did they know what the Navy and Marines had in store for them.

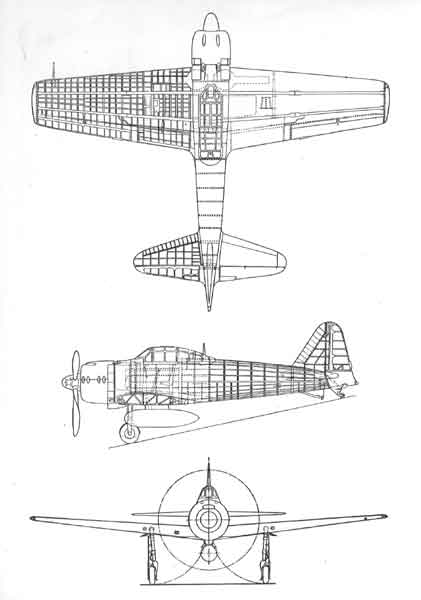

The Zero’s two cowl-mounted 7.7mm machine guns were not particularly effective, especially against the new generation of heavy, over built U.S. fighters. At little more than half the calibre of the American .50s, they were used by many Zero pilots mainly as “pointers” for their cannons; if they saw hits from the machine guns, they toggled the cannons alive and fired them instead. Just like a World War I Spad or Fokker, the Zero’s 7.7mm receivers were in the cockpit, above the instrument panel on either side, or the pilot pulled levers to charge them. Some say that because the Zero was the best dogfighter in the Pacific theatre, perhaps the world, it was by definition the best fighter. But there’s an old saying in auto racing, “To win, you have to finish.”

So praising the Zero’s manoeuvrability is a bit like saying a racecar is the best in the world because it’s the fastest, even if it can’t finish more than 10 laps of a track before having a mechanical failure and being beaten to the checkered flag by a slower car. Ultimately, the Zero’s main failing was that it was designed to a 1930s paradigm: Air combat meant dogfighting, and dogfighting, at least in the days before energy management, meant a circle-chase, in one form or another, with the better airplane turning tighter than the lesser one and eventually getting into a firing position from a rear quarter. Victory was then nearly inevitable.

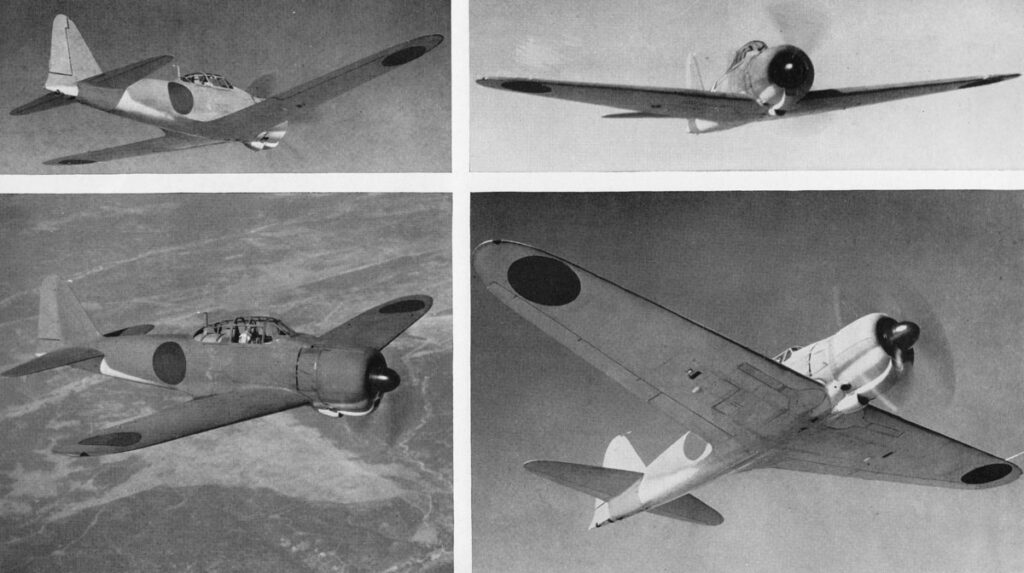

The Zero was the world’s tightest-turning, most manoeuvrable fighter. Thanks to its aerobatic ability, Zero pilots also developed a combat manoeuvre that initially baffled American airmen: a kind of sideways loop with square turns and side-slips out of the turns, which tightened the turn greatly. A typical multi-plane Zero attack was a melee of individual aerobatics, and Japanese pilots were in nearly as much danger of mid-air’s with their mates as they were of getting shot at. As one USN pilot put it, “From the way the Zero pilots rollicked around the sky, at times it looked as though they would rather stunt than fight.” “Yonekawa…flew upside down, waving both hands around in the cockpit,” wrote Sakai in his book Samurai. “Then he flew directly over me, under me, and went through a wide hesitation roll around my fighter. He was like a kid showing off. He finally flew on my wing and held the stick between his knees. Still grinning, he waved his lunchbox at me and started to eat.”

It didn’t take long, however, for American pilots to learn that rat-racing with a Zero was a loser’s game, so they disdained tail chases that played straight into the Zero’s only air combat strength; it was neither strong, unusually fast, good in a dive nor effectively armed. Hit and run became the mantra: Attack a Zero from above, fire while diving upon it and then keep going. Convert diving energy to zooming altitude and do it again, if necessary. Perhaps it was inevitable that the Zero would become a myth, a legend, a paragon among fighters when it was in fact a conventional airplane with several ahead-of-its-time characteristics.

It could be argued that the Zero was an excellent airplane but a lousy fighter. After flying a Zero, the highly respected Curtiss test pilot H. Lloyd Child even suggested that “a commercial version of it would appeal to a sportsman pilot after the war. Its clean lines, simplicity, lightness and ease of handling…would make this a desirable airplane for a millionaire private owner.”

*Originally published in the July 2012 Issue of Aviation History Magazine.

Be the first to comment